Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Human Rights & Science (JMSHRS)

Volume 7, Issue 3, Special Issue on Deflection - II - 2025 | SDGs: 3 | 5 | 10 | 16 | #RethinkProcess ORIGINAL SOURCE ON: https://knowmadinstitut.org/journal/

DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.15222574

Volume 7, Issue 3, Special Issue on Deflection - II, April 2025 | SDGs: 3 | 5 | 10 | 16 |

DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.15222574

Preventing Substance Use-Related Crime

through Deflection

Guy Farina*

Jac A. Charlier

Hope Fiori

EN | Abstract:

This article examines deflection as a crime prevention strategy that focuses predominantly on preventing offenses related to substance use and co-occurring disorders. Applying decades of lessons learned in crime prevention, public health, community policing, and harm reduction, deflection brings together law enforcement and community partners to improve community safety and advance public health. The authors’ literature review found that deflection is effective in reducing drug use-related criminal activity, arrest, recidivism, and overdose risk, while also serving as a promising approach to reduce social and public safety costs.

Key Words: Deflection, Crime Prevention, Public Health, Community Policing, Harm Reduction, Substance Use, Co-Occurring Disorders, Recidivism, Overdose, Community Safety, Criminal Justice, SDG 1, SDG 3, SDG 5, SDG 10, SDG 16, SDG.

ES | Abstract:

Este artículo examina la deflexión como una estrategia de prevención del delito que se enfoca principalmente en evitar delitos relacionados con el consumo de sustancias y los trastornos concurrentes. Aplicando décadas de aprendizajes en prevención del delito, salud pública, policía comunitaria y reducción de daños, la deflexión reúne a las fuerzas del orden y a los socios comunitarios para mejorar la seguridad pública y promover la salud pública. La revisión de la literatura realizada por los autores encontró que la deflexión es efectiva para reducir la actividad delictiva relacionada con el consumo de drogas, los arrestos, la reincidencia y el riesgo de sobredosis, además de representar un enfoque prometedor para disminuir los costos sociales y de seguridad pública.

Palabras clave: Deflexión, Prevención Del Delito, Salud Pública, Policía Comunitaria, Reducción De Daños, Uso De Sustancias, Trastornos Concurrentes, Reincidencia, Sobredosis, Seguridad Comunitaria, Justicia Penal, ODS 1, ODS 3, ODS 5, ODS 10, ODS 16, ODS.

INTRODUCTION

Deflection is a community-based crime prevention strategy whereby law enforcement and community partners work together to address individuals’ substance use disorders (SUDs) before justice system involvement becomes necessary.

The practice of deflection is growing quickly across the United States, and also in the United Kingdom, Ireland, Kenya, Mexico, South Africa, Italy, Tanzania, and multiple other countries in Africa, the Americas, Asia, and Europe, as communities seek effective means to prevent substance-related offenses. The research and lessons presented in this article are derived primarily from data in the United States, as that is where deflection-related information is currently most readily available and in the greatest quantity. Data and evaluations from other countries are now beginning to appear and will be used for a follow-up article.

I. NEXUS BETWEEN SUBSTANCE USE AND CRIME

In the United States, police officers long have come in contact with people using addictive substances. Drugs were virtually unregulated until the early 1900s, as drug use and treatment were considered private matters. Since the late 1910s—and most prominently during the eras of Prohibition (1920–1933) and the “war on drugs” (beginning in 1971 and ongoing)—drug laws have been enacted and enforced with great variability (Courtwright, 1992). As a recent snapshot, law enforcement agencies in the U.S. reported making 907,958 arrests for drug offenses in 2022, with drug possession accounting for 797,187 (87.8%) of these arrests (Drug Policy Facts, 2024; Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2024).

Law enforcement officers often encounter people engaged in lower-level offenses who have SUDs (Zhang et al., 2022). Over the past half-century, police have generally used one of two options in these instances: arrest the individual or take no action—with neither option addressing the underlying issues. Deflection offers a third option: connecting people to SUD treatment and other community-based services before an event such as an overdose, arrest (with charges being filed), or mental health crisis occurs (Police, Treatment, and Community Collaborative, 2023). This linkage to care happens at the point of contact with first responders, which can be during a call for service, after an overdose, as follow-up from previous non-arrest police encounters, or by self-referral of the individual.

Several common types of offenses directly or indirectly involve drugs, including possession, distribution, and offenses committed to get money for drugs, especially property offenses (Andraka-Christou, 2016; International Centre for the Prevention of Crime, 2015; Taxman et al., 2004). And, continued substance use is an illegal act itself for individuals under criminal justice supervision. Further, even when a substance is legal (such as alcohol or, in a growing number of U.S. states, marijuana) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], February 2024) or decriminalized in some form (again, such as marijuana), the consequences of a person’s SUD can affect the larger community and lead to justice system involvement, given that the legal status of a substance does not change addictive properties such as cravings and withdrawal, which are often directly related to criminal behaviors associated with drug use.

Multiple research studies have demonstrated the prevalence of substance use among people who have been arrested and incarcerated. As examples, a 2017 Bureau of Justice Statistics study found that about 40 percent of convicted individuals in U.S. jails and state prisons had used drugs at the time of their offense. Additionally, about 40 percent of those who were incarcerated for property offenses had committed the crime to get money for drugs or to obtain drugs (Bronson, 2020).

“Drug addiction… like liquor, is not a police problem; it never has been and never can be solved

by policemen [sic]. It is first and last a medical problem, and if there is a solution it will be

discovered not by policemen [sic], but by scientific and competently trained medical experts...”

– August Vollmer (1876-1955), who became known as the “father of modern American policing”

(Vollmer, 1936, as cited in Oliver, 2017) |

ADDRESSING SUBSTANCE USE AS A CRIME PREVENTION STRATEGY

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, “‘crime prevention’ comprises strategies and measures that seek to reduce the risk of crimes occurring, and their potential harmful effects on individuals and society, including fear of crime, by intervening to influence their multiple causes” (United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime, 2002). Crime prevention strategies address SUD as a criminogenic need, meaning it is one of the factors associated with committing or re-committing an offense (Wooditch et al., 2014).

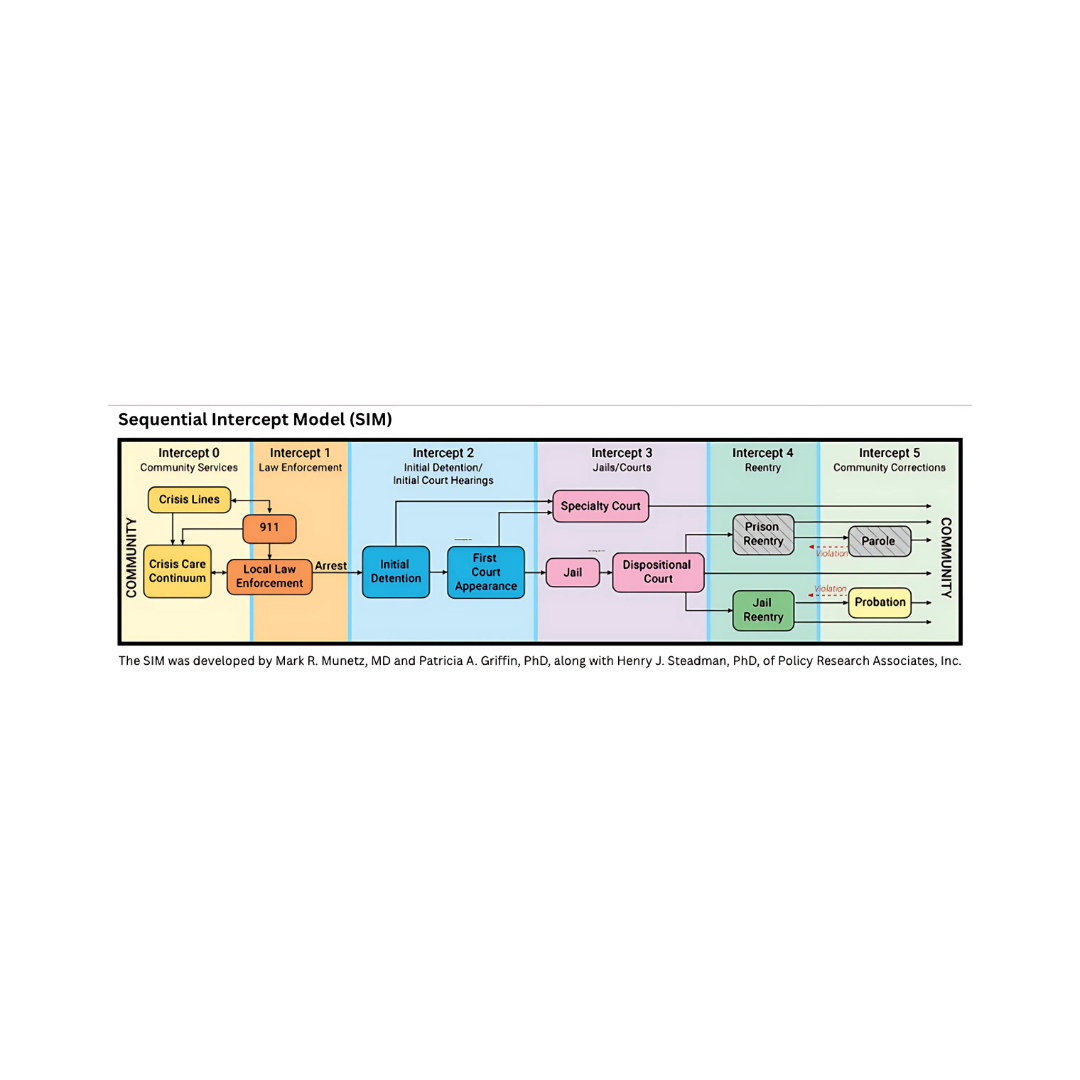

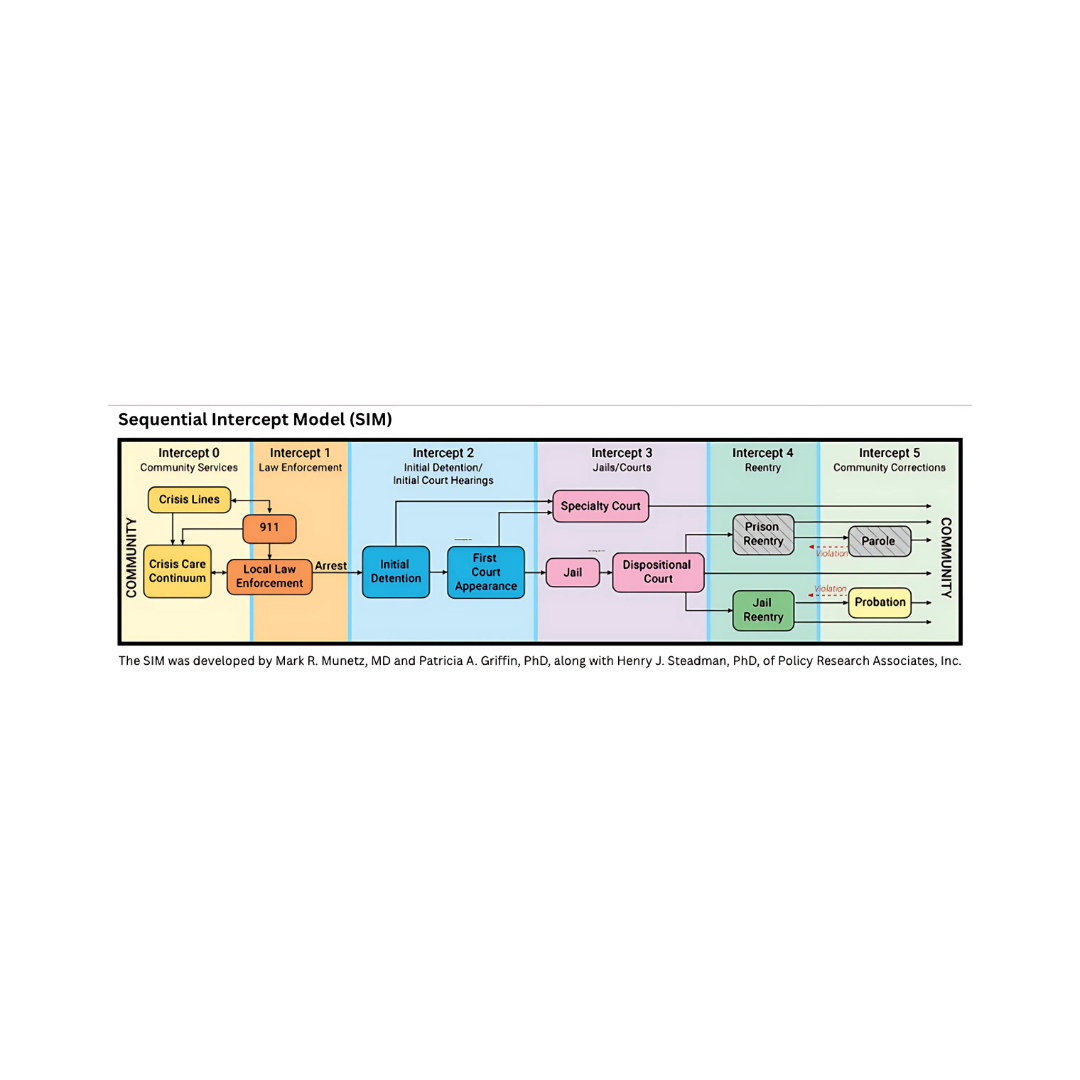

To be clear, not everyone who might be arrested for a substance-related offense should be deflected away from entry into the justice system (e.g., those suspected of violent crimes, which by definition involve force or the threat of force, such as gun offenses, sexual assault, domestic violence, criminal enterprise activity, and illicit drug manufacturing and trafficking). The Sequential Intercept Model (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2024b) serves as a planning tool to help justice system and community stakeholders determine which strategies to consider at each stage of the system, from pre-arrest to post-release, in order to appropriately address the clinical needs of the individual as well as the public safety needs of the community. Because deflection happens in the community before individuals enter the system—at Intercept 0 or Intercept 1 in the Sequential Intercept Model—deflection offers the greatest opportunity to reach the most people and at an earlier stage than was previously common.

REACHING INDIVIDUALS AT RISK FOR FREQUENT, LOWER-LEVEL OFFENSES

Deflection is a pro-active strategy to address the needs of people who are, or may become, “frequent utilizers” of the justice system due to their SUDs and/or mental health conditions. Of the at least 4.9 million people arrested and jailed in the U.S. each year, at least 25 percent are booked into jail more than once during that year. More than half (52%) of people arrested multiple times reported an SUD in the past year, compared to only seven percent of people who were not arrested. Those with multiple arrests also were three times more likely to have a serious mental illness compared to those with no arrest (Jones, 2019).

While people arrested multiple times in a year disproportionately have underlying health needs leading to police contact, at the same time, the vast majority do not pose a serious public safety risk. Eighty-eight percent of those arrested and jailed multiple times in a year had not been arrested for a serious violent offense in the past year (Jones, 2019). Deflection eases the burden that “frequent utilizers” place on law enforcement and the justice system while assuring access to treatment for the underlying SUD.

Important for building trust between police and the community, deflection strategies can begin to reverse the negative consequences of the drug war approach, which has created wide disparities in terms of jailing of people in poverty, and, in the United States, predominantly Black people, including those experiencing a substance use and/or mental health disorder (Jones, 2019; Pew, 2023). Deflection is designed to help people access services in lieu of being arrested and entering the system, and offers strategies specifically to enhance equity.

Finally, two foundational ideas in deflection are accountability and preventing crime victimization. Those who use drugs and alcohol are still accountable for their actions; that does not change. Deflection does not seek to remove accountability, but rather seeks to ensure that by reaching the person earlier and by offering community-based treatment alternatives, their ability to stop using drugs is increased. Evidence shows that when people with SUDs stop using drugs, their criminal behaviors decrease (Chandler et al., 2009). As a result, the number of people who would otherwise become victims of crime also decreases. This includes homes and businesses that might become the target of burglaries and property crimes, which, as a result of deflection, do not happen.

COSTS AND CONSEQUENCES OF OVERLY PUNITIVE APPROACHES

Modern policing in the United States has been described in three eras: the Political Era (1840s to early 1900s), so named because of the political influence intertwined with policing (Hartmann, 1988); the Reform Era of the early (1900s to 1970s, including the professional advances led by August Vollmer); and the Community Era beginning in 1980 and emphasizing the role and partnership of the community in problem-solving (CommunityPolicing.com, n.d.).

Meanwhile, specific to the policing of addictive substances, in 1971 President Richard Nixon declared a “war on drugs,” which dramatically increased arrests, prosecution, and incarceration for drug-related offenses. For decades, this approach caused skyrocketing incarceration rates without resulting in comparable reductions in crime and drug use (Gainsborough & Mauer, 2000; Pew, 2018).

Indeed, strictly punitive approaches often have proven to be more harmful than helpful. Arresting and incarcerating individuals with SUDs does not address the underlying health condition, and in fact a person’s very entry into the criminal justice system increases their risk for recidivism (Yukhnenko et al., 2020). Furthermore, as policing pioneer Sir Robert Peel emphasized in the 19th century, the balance with individual liberty is paramount in policing (Law Enforcement Action Partnership [LEAP], n.d.). The drug war approach has disrupted this balance (Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2022; Vitiello, 2021) and in many places, community trust with it (Morrison, 2021; Olson, 2016).

SUPPORTING HUMAN RIGHTS

Mitigating the widespread and damaging impacts of punitive-only approaches, deflection supports human rights by identifying and treating root issues related to criminal activity and poor health such as SUDs, mental health disorders, trauma, and co-existing disorders, while also preventing unnecessary entry into the justice system for those who do not present a risk to public safety. Deflection ensures individuals’ rights to health and dignity while promoting a justice system that is fair, restorative, and accountable.

Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights asserts every individual’s right to health and well-being, including access to medical care and necessary social services (United Nations General Assembly, 1948, as cited in United Nations, 2021). Deflection embodies this principle by prioritizing treatment over punishment-only approaches without compromising public safety for individuals with substance use issues. These programs focus on supporting vulnerable populations, such as those affected by poverty, community disenfranchisement, and gender-based violence, offering resources and rehabilitation as a first approach to addressing drug use, misuse, and addiction. In this way, deflection also can help reduce costly incarceration rates by serving as an effective alternative to incarceration for minor, non-violent offenses related to personal drug use. Given this, deflection also is an ideal strategy for addressing youth involved in drug use and related non-violent criminal behavior (Police, Treatment, and Community Collaborative, 2024). Finally, deflection aligns with the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Sustainable Development Goal 16 (UNODC, n.d.) by promoting peace, justice, and strong institutions through restorative justice, enhancing community trust and accountability.

II. BUILDING ON LESSONS LEARNED IN PUBLIC HEALTH AND PUBLIC SAFETY

Knowledge and advances in the following areas during the past several decades, combined together, underlie the practical basis for deflection.

THE SCIENCE OF ADDICTION

The use of substances—including alcohol and a wide range of both legal and illegal drugs—can range from “non-pathological” (not causing harm) to a diagnosed disorder (Ramey & Regier, 2018). An SUD affects the brain and behavior, affecting executive functions, decision-making, impulsivity, and self-regulation/risk-taking (Krmpotich et al., 2015). Addiction is a severe SUD characterized by compulsive and continued use despite negative consequences (Ramey & Regier, 2018).

Science has progressed to a point where we can see the neurobiological effects of addiction in brain images (Uhl et al., 2019). Simply, addiction hijacks the brain's reward system. Drugs and alcohol trigger the release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter that produces feelings of pleasure. Substances overstimulate certain systems in the brain creating a stronger-than-normal association between the drug and pleasure. Repeated drug use diminishes the individual's ability to feel pleasure from natural rewards. This adaptation drives people to seek out drugs compulsively, despite negative consequences (Yale Medicine, 2022). Also, the part of the brain that governs decision-making, self-control, and judgment is significantly impaired in individuals with addiction. This makes it harder for them to resist cravings or make rational decisions, reinforcing compulsive drug-seeking behavior (Verdejo-García et al., 2006).

This understanding of what addiction does to the brain illustrates how compulsive drug use can lead to drug-related offenses. An arrest does not address the underlying motivation and behavior related to the offense. As an analogy, a cough can be a symptom of the flu. Cough medicine may temporarily relieve the cough, but the cough is likely to return unless the flu itself is treated. Likewise, a crime driven by addiction is a symptom of the SUD, but the problem to be addressed is the SUD itself.

TREATMENT AND RECOVERY

As with other chronic health conditions, different treatment approaches work best for different individuals. Treatment may include outpatient or residential services, individual or group therapy, medications, or a combination of these (SAMHSA, 2023). (Detoxification alone is not treatment, but it may serve as an entry point for a person transitioning to treatment; Timko et al., 2016).

Scientific discoveries regarding addiction’s impact on the brain have critical implications for treatment and rehabilitation. Medical SUD treatment has been shown to restore the balance of the brain circuits and lead to behavioral improvements. Additionally, certain medications can help prevent relapse while the individual is learning, or relearning, healthy decision-making and emotional regulation (Volkow et al., 2016).

Without intervention and treatment, addiction tends to worsen over time (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General, 2016). However, recovery is possible at any stage, and with proper treatment and support, individuals can regain control of their lives. Recovery is a long, complex process that requires time and perseverance; slips or relapses are not uncommon. Rather than indicating failure, however, these setbacks are often part of the journey, providing opportunities for reflection, adjustment, and continued progress toward long-term sobriety.

As the beginning phase of long-term recovery, treatment must address issues that directly relate to (re)committing a crime (i.e., the criminogenic needs). By doing so, research consistently has demonstrated that community-based SUD treatment can reduce drug use and drug-related criminal behavior (Chandler et al., 2009).

CHILDHOOD TRAUMA

While mental health issues by themselves are not considered to directly lead to crime (Petis, 2024), people with mental health disorders disproportionately come into contact with law enforcement compared to the general population (SAMHSA, 2024a). Research on trauma and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) underscores the connection between early life challenges and criminal behavior; childhood trauma such as abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction are strongly linked to substance use and criminal behavior later in life (Baglivio, 2014; Hartman, 2008; Nembhard, 2022; Widom, 1989).

These early traumatic experiences disrupt brain development, particularly in areas that regulate emotions and decision-making, making individuals more prone to using substances as a way to cope with emotional pain or stress. The cumulative impact of childhood trauma also increases the risk of addiction and involvement in crime as unresolved trauma can lead to impulsivity, aggression, and antisocial behavior (Dargis, 2016).

Recognizing and addressing these underlying issues through trauma-informed care and early intervention is crucial in preventing and treating both SUDs and criminal conduct.

When law enforcement chooses to deflect rather than arrest, they attack drug-related crime and drug-seeking behavior at its root, addiction. Deflection shows promise to be able to go even further by addressing the cause of the addiction, in many cases, which is the trauma that preceded it.

HARM REDUCTION

Harm reduction—as one component of a continuum of care that includes engagement, treatment, and medications—is an evidence-based approach that offers people who use drugs resources and information to reduce their risks and potentially save their lives (CDC, April 2024). Implementing harm reduction strategies through community and police partnerships helps to reduce the harm to the community of criminal acts, while also promoting the health of the individual and the community.

Harm reduction is not a new concept in the criminal justice system. Practices such as restorative justice, victim impact panels, victim impact statements during sentencing, and restitution all aim to minimize the harm caused by certain crimes. Similarly, the use of overdose reversal supplies, substance test kits (like fentanyl test strips), wound care supplies, and medication lock boxes are harm reduction tools that specifically address the harm of drug-related crimes. These approaches are part of a comprehensive deflection initiatives, aimed at mitigating the negative consequences of both crime and substance use.

COMMUNITY POLICING

To effectively deal with criminal behavior associated with drug-related crime, police, other first responders, and treatment professionals must work together. A bridge between police and treatment is needed, and deflection draws on 40 years of lessons from community policing to create that bridge.

While community policing means different things to different communities and its implementation varies throughout the nation (Maguire, 2009, p. xv), it is, “in essence, a collaboration between the police and the community that identifies and solves community problems” (Bureau of Justice Assistance, 1994). Indeed, partnership building is the first of the five critical elements of successful first responder deflection programs (COSSUP, 2020).

Effective community policing also demonstrates that addressing underlying social issues such as poverty, addiction, and mental health through partnerships can reduce crime more sustainably than reactive enforcement. In other words, pro-active support is preferred over punishment.

The goal is preventing crime, not catching criminals. If the police stop crime before

it happens, we don’t have to punish citizens or suppress their rights. An effective

police department doesn’t have high arrest stats; its community has low crime rates.

– A core idea of Sir Robert Peel (1788–1850), who established the first organized

police force in London in 1829 (LEAP, n.d.) |

III. EFFECTIVENESS OF DEFLECTION

The discipline of connecting individuals to treatment as an alternative to arrest has been practiced formally in the United States since 2011 (Legislative Analysis and Public Policy Association [LAPPA], 2023). Describing this practice, the term “deflection” was first introduced into the justice field in a 2015 Police Chief magazine article entitled “Want to Reduce Drugs in Your Community? You Might Want to Deflect Instead of Arrest,” published by the International Association of Chiefs of Police (Charlier, 2015).

The preponderance of available deflection data emanates from the U.S., as presented further below. And although not necessarily so named, the practice is gaining traction and showing success in a number of countries.

For instance, in the United Kingdom, particularly in Thames Valley, deflection approaches are referred to as “diversion schemes” or fall under “out-of-court disposals.” The Thames Valley Deflection Program, run by the Thames Valley Police and the Violence Reduction Unit, directs individuals to support services such as addiction treatment, mental health care, and social services. This approach has significantly improved outcomes, lowering reoffending rates while providing individuals with critical support (Centre for Justice Innovation, 2020; College of Policing, 2022). In addition, the Thames Valley Police report significant time savings, estimating that a possession offense consumes approximately 12 hours of police time, compared to only 20 minutes to deflect someone (Transform Drug Policy Foundation [TDPF], n.d.).

In Durham, UK, a similar initiative deflects individuals who have low-level offenses, including possession of illicit drugs. This initiative, known as Checkpoint, has reported lower rearrest and reoffending rates among participants compared to those receiving other out-of-court disposals such as cautions or conditional cautions (TDPF, n.d.).

In British Columbia (BC), Canada, decriminalization efforts include deflecting people who use drugs away from the justice system and toward health and social supports. Pursuant to these aims, key metrics for law enforcement include reducing the number of personal possession related offenses. From 2019 to 2022, the number of simple possession charges recommended by BC police declined by 87 percent (British Columbia Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions, 2024, pp. 5, 14).

Portugal’s 2001 decriminalization of all drugs offers a different model, where individuals caught with personal-use quantities are referred to “Dissuasion Commissions” for evaluation by legal and health professionals instead of being arrested. These commissions operate independently from the criminal justice system. “For people who appear to use drugs frequently and problematically, the Commissions will make referrals to treatment, which is always voluntary and never mandated. If people with substance use disorder opt not to enter treatment, administrative sanctions – such as the revocation of a driving license or community service – can be applied, but rarely are” (Drug Policy Alliance, 2023, p. 4). The numerous impacts of Portugal’s decriminalization approach include significant increases in voluntary admissions to treatment, coupled with substantial decreases in overdose deaths, HIV infections, problem drug use, and incarceration for drug-related offenses (Drug Policy Alliance, 2023, p. 2).

DEFLECTION OUTCOMES IN THE UNITED STATES

Outcomes from deflection programs across the U.S. have shown their effectiveness in reducing substance use-related criminal activity (Korchmaros & Bentele, 2022, p. 23), preventing criminal recidivism, reducing arrest, and reducing overdose risk, along with their promise for improving health outcomes, reducing social and public safety costs, and improving police-community relations (Labriola et al., 2023; Reichert, Adams, et al., 2023).

The National Association of Counties (NACo) examined reports from a number of deflection programs across the country, finding that while punitive approaches to people with SUD were associated with increased risks for future arrest and overdose, deflection programs: reduced recidivism and re-arrest, reduced overdose risk, produced significant cost savings, and improved participants’ well-being, particularly in terms of accessing housing, meeting basic survival needs such as food and clothing, and addressing SUD and mental health concerns (Carroll, 2024).

Similarly, a multi-site evaluation of the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) initiative in four North Carolina communities found that their deflection initiative: higher program engagement among participants was associated with greater reductions in arrests and citations, as well as increased use of medication-assisted treatment, compared with people who had little or no program engagement. Regardless of their level of engagement, people referred to LEAD had a one-third decrease in the rate of citation/arrest events in the six months after referral, compared to people with similar drug charges who were eligible but not referred. Additionally, for program enrollees there was a 50 percent reduction in crisis-related services in the six months after their referral, whereas those costs doubled among people who were referred but chose not to enroll (Gilbert, 2023).

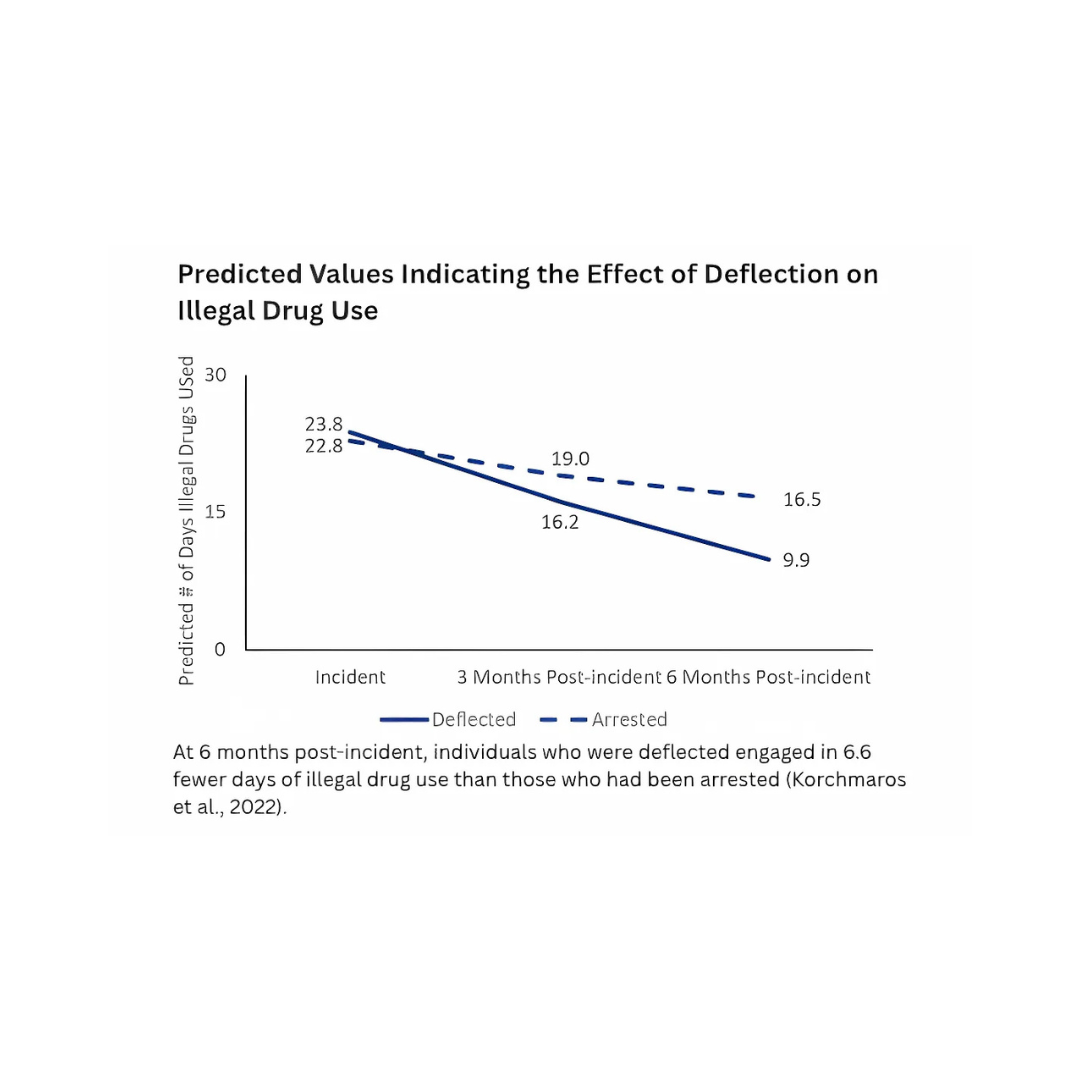

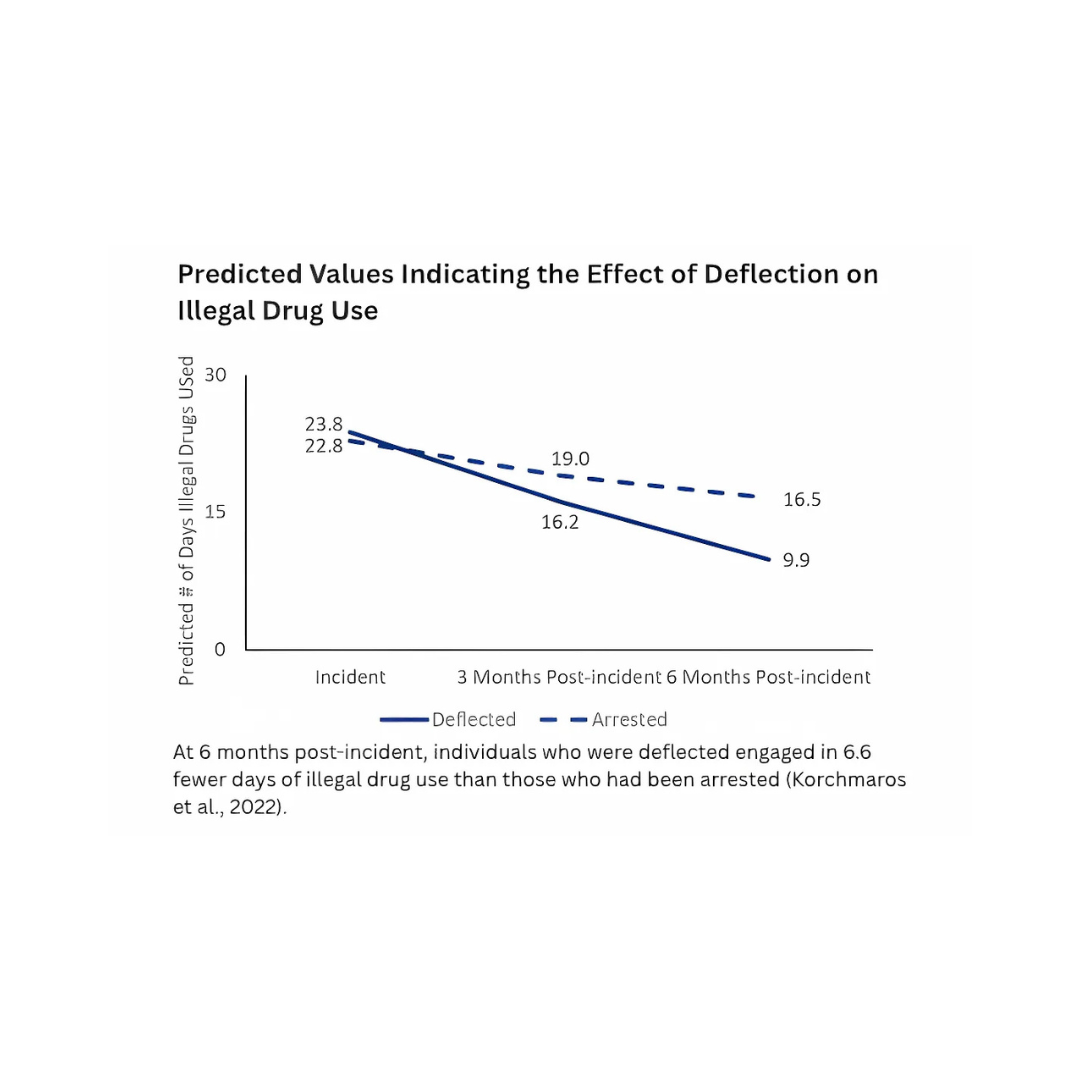

Studies of individual deflection initiatives have found the same. In the Tucson Deflection Initiative (TDI) in Arizona, for instance, deflection was more effective than arrest in reducing frequency of illegal drug use. Mental health issues, employment stability, housing stability, and treatment readiness, in combination with AOD [alcohol and other drugs] use at time of incident, also impacted change over time in frequency of illegal drug use (Korchmaros et al., 2022).

In the Madison Area Recovery Initiative (MARI) in Wisconsin, individuals who completed the deflection program were less likely to be re-arrested, incarcerated, or experience a fatal overdose compared to those who did not engage in the program. Based on 263 participants enrolled between September 2017 and August 2020, 12-month follow-up data revealed that those who did not engage in MARI or did not complete the program were 3.9 and 3.6 times, respectively, more likely to be arrested and 10.3 and 21.0 times more likely to be incarcerated, compared to those who completed the program. Additionally, 5.8% and 3.3%, respectively, had a fatal overdose, compared to 2.0% of those who completed MARI (Nyland, 2024).

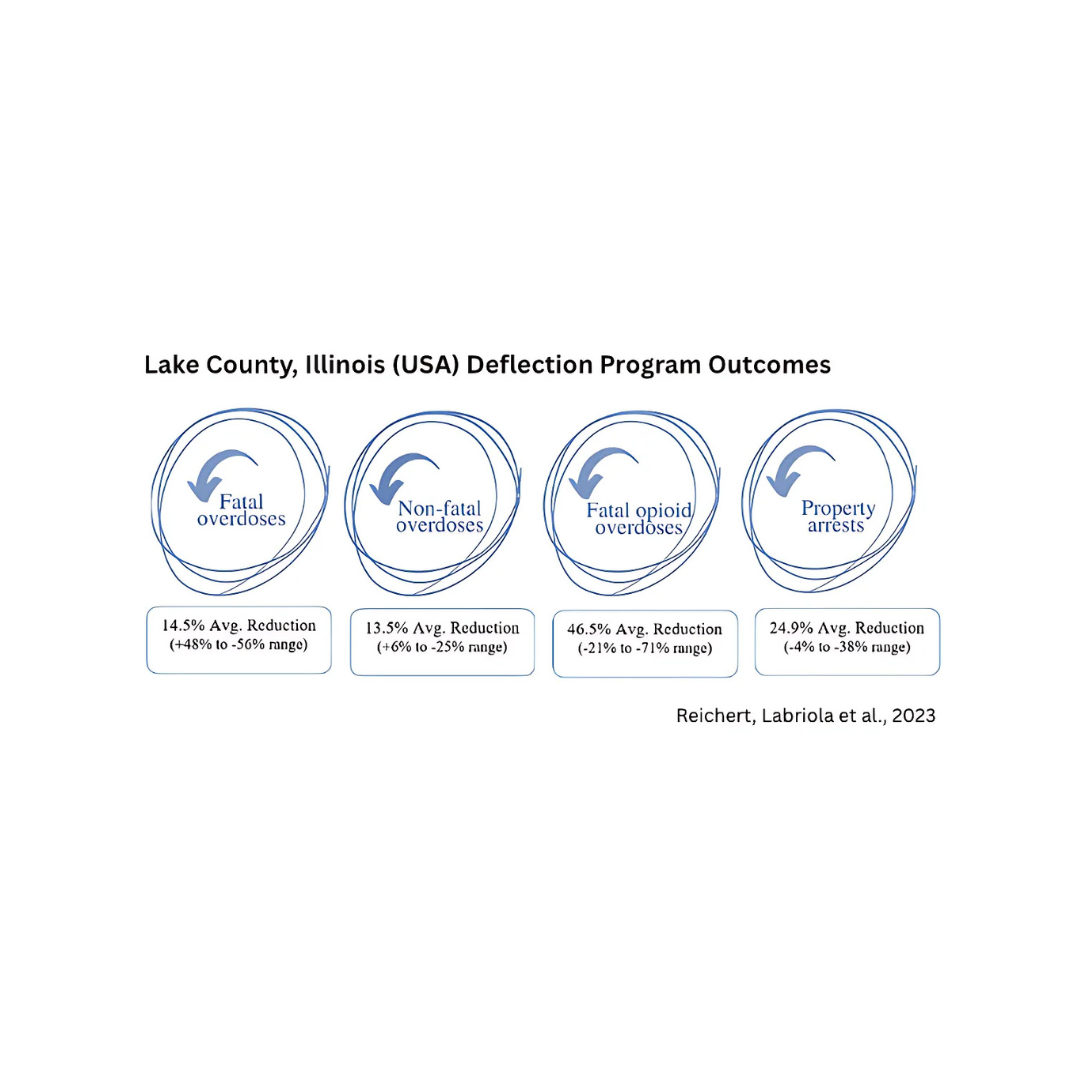

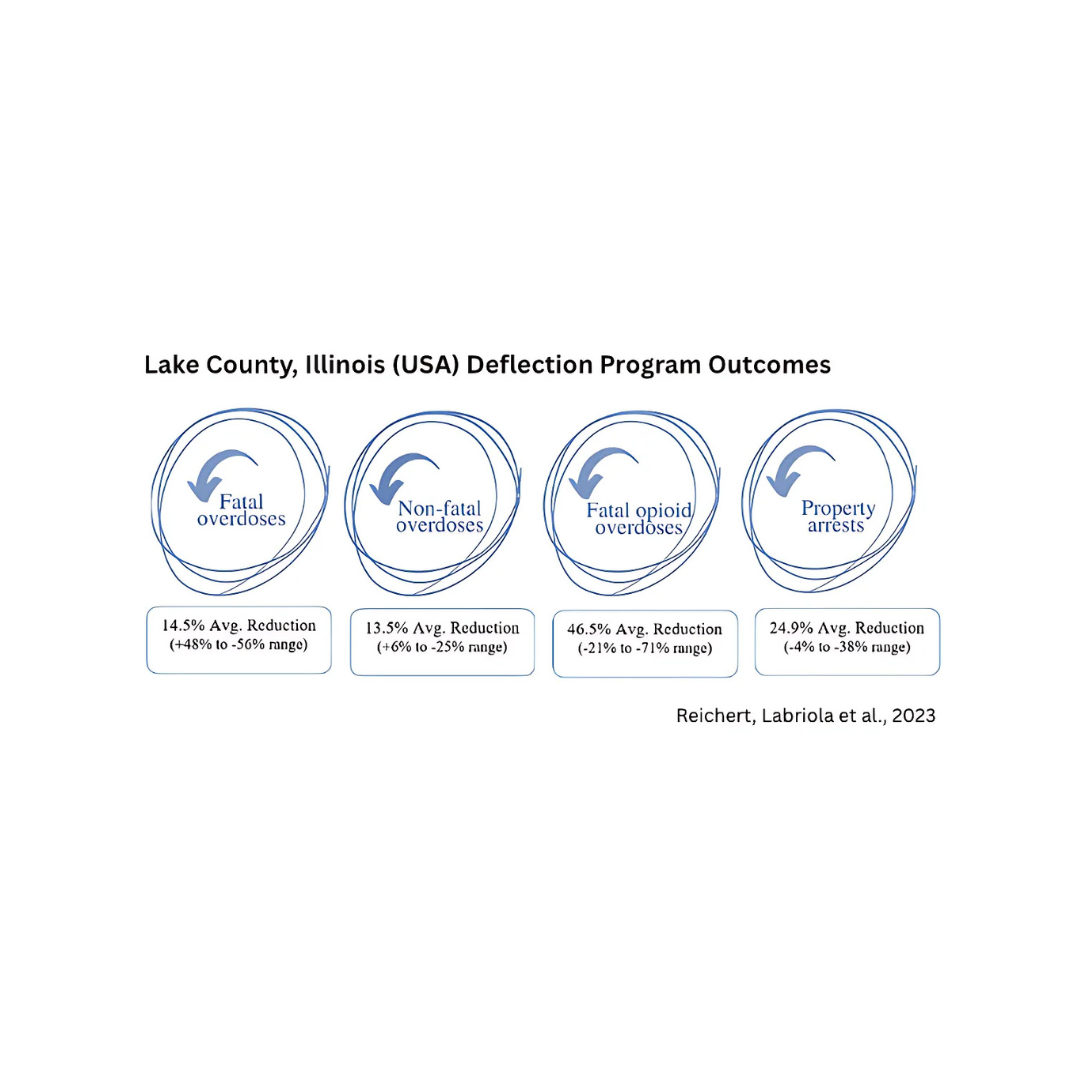

In Lake County, Illinois, an evaluation of the impact of the A Way Out deflection program from 2016 to 2020, on average: fatal overdoses decreased 14.5 percent; non-fatal overdoses decreased 13.5 percent; fatal opioid overdoses decreased 46.5 percent, and property crime arrests dropped 24.9 percent (Reichert, Labriola, et al., 2023).

Likewise, an analysis of initiatives in Pima County, Arizona and Charleston County, South Carolina found that deflection programs lower re-arrest rates by addressing underlying issues such as substance use and mental health; these approaches can reduce the financial burden on the criminal justice system by decreasing incarceration rates; and by connecting individuals to treatment instead of arrest, communities experience safer environments and strengthened police-community relations (Magnuson et al., 2022).

Finally, and critically, using deflection as a performance metric is essential for officer buy-in and support (IACP, 2024). Deflection does not discount the importance of making arrests when necessary and, as has been previously stated, does not relieve individuals of the accountability for their actions, but rather it presents an option that can support and incentivize officers in completing training and making connections to treatment and other services (Reichert et al., February 2023).

IV. A CALL TO ACTION

From its start just over a decade ago, deflection is now recognized by nine U.S. federal agencies: the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA), National Institute of Justice (NIJ), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), Veterans Administration (VA), Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP), and the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL). Additionally, deflection teams in the U.S. are now active in 41 of the 50 states, with 17 states having established some form of state-level funding, practice, policy, or evaluation specifically related to deflection (Charlier, 2023.) And, as described previously, its growth continues in other countries as well.

To guide and support the continuing development of deflection initiatives, the following three recommendations are proposed:

POLICY RECOMMENDATION 1

Launch a deflection pilot initiative within your country, region, or area. Testing a new approach is one of the most effective ways to assess its viability. Recognizing that each country operates within a unique legal framework, the recommendation is to start small. This begins with convening police, treatment providers, and community leaders to explore how deflection could be implemented in that community's specific context. Deflection serves as a bridge between systems, and these initial conversations lay the foundation for building that bridge.

POLICY RECOMMENDATION 2

Develop a legislative and policy framework to support deflection in your region or municipality (e.g., country, province, township, city, etc.). This should include securing funding, establishing mechanisms for data collection and evaluation, enhancing administrative capacity, promoting first responder well-being, and advancing workforce development. These elements are essential for effective public policy. As the pilot progresses, focusing on these areas will prepare the country for scaling deflection to a national or regional level. As a guiding resource, the Legislative Analysis and Public Policy Association (LAPPA) in the U.S. has developed the, Model Law Enforcement and Other First Responder Deflection Act, which offers baseline considerations for policy development (LAPPA, 2021).

PUBLIC AWARENESS RECOMMENDATION

Share success stories of deflection with elected officials and the public, highlighting perspectives from law enforcement, treatment and recovery professionals, community members, and participants in the deflection program. While not strictly a policy recommendation, raising public awareness and promoting the value of deflection is critical to creating a fertile environment for its growth and expansion.

Deflection offers a new space for actionable, community-based solutions that exist between prevention and diversion (which itself is centered in the justice system), creating new opportunities to reduce drug use and drug-related crime. This evolution is exciting, and of great interest to communities, policymakers, and practitioners alike. What have traditionally been the worlds of drug demand reduction and drug supply reduction working separately and apart from one other can now be bridged through deflection. This is necessary for a very simple reason: they need one another to do more impactful work that they cannot do alone.

REFERENCES

- Andraka-Christou, B. (2016, July). Social & legal perspectives on underuse of medication-assisted treatment for opioid dependence. [Doctoral dissertation, Indiana University Maurer School of Law, 31]. https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/etd/31/

- Baglivio, M. T., Epps, N., Swartz, K., Huq, M. S., Sheer, A., & Hardt, N. S. (2014). The prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACE) in the lives of juvenile offenders. Journal of Juvenile Justice, 3(2), 1–23. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/scans/Prevalence_of_ACE.pdf

- British Columbia Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions. (2024, November). Decriminalization data report to Health Canada. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/overdose-awareness/data_report_to_health_canada_november_2024.pdf

- Bronson, J., Stroop, J., Zimmer, S., & Berzofsky, M. (2020, August 10). Drug use, dependence, and abuse among state prisoners and jail inmates, 2007-2009: Special report. Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice. (Original work published 2017) https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/dudaspji0709.pdf

- Bureau of Justice Assistance. (1994). Understanding community policing: A framework for action. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles/commp.pdf

- Carroll, J. (2024, July). Pre-arrest diversion: A NACo opioid solutions strategy brief. National Association of Counties. https://www.naco.org/sites/default/files/2024-07/NACo_OSC_PreArrest%20Diversion.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, February 16). State medical cannabis laws. https://www.cdc.gov/cannabis/about/state-medical-cannabis-laws.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, April 16). OD2A case study: Harm reduction. CDC Overdose Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/overdose-prevention/php/od2a/harm-reduction.html

- Centre for Justice Innovation. (2020.) Thames Valley drug diversion scheme. https://justiceinnovation.org/project/thames-valley-drug-diversion-scheme

- Chandler, R. K., Bennett W Fletcher, B. W., Volkow, N. D. (2009, January 14). Treating drug abuse and addiction in the criminal justice system: Improving public health and safety. JAMA, 301(2), 183–90. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2008.976

- Charlier, J. (2015, September). Want to reduce drugs in your community? You might want to deflect instead of arrest. Police Chief. International Association of Chiefs of Police. https://www.policechiefmagazine.org/wp-content/uploads/Policyreform_September2015.pdf

- Charlier, J. (2023, October 3). Opening national plenary [Conference presentation]. PTACC 2023 National Deflection & Pre-Arrest Diversion Summit, Denver, CO, United States.

- College of Policing. (2022, October 19). Police-led diversion. https://www.college.police.uk/guidance/drug-crimes-evidence-briefing/police-led-diversion

- CommunityPolicing.com. (n.d.) History of policing. https://www.communitypolicing.com/criminal-justice

- Comprehensive Opioid, Stimulant, and Substance Use Program. (2020, December). Critical elements of successful first responder diversion programs. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Assistance. https://www.cossup.org/Content/Documents/Articles/CHJ_TASC_Critical_Elements.pdf

- Courtwright, D. (1992). A century of American narcotic policy. In D.R. Gerstein & H.J. Harwood (Eds.), Treating drug problems: Volume 2: Commissioned papers on historical, institutional, and economic contexts of drug treatment. Institute of Medicine (U.S.) Committee for the Substance Abuse Coverage Study. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK234755/

- Dargis, M., Newman, J., & Koenigs, M. (2016). Clarifying the link between childhood abuse history and psychopathic traits in adult criminal offenders. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 7(3), 221-228. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000147

- Drug Policy Alliance. (2023). Drug decriminalization in Portugal: Learning from a health and human-centered approach. https://drugpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/dpa-drug-decriminalization-portugal-health-human-centered-approach_0.pdf

- Drug Policy Facts. (2024). Total annual drug arrests in the United States by offense type. Real Reporting Foundation. https://www.drugpolicyfacts.org/node/234

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2024). Crime Data Explorer. https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/explorer/crime/arrest

- Gainsborough, J. & Mauer, M. (2000). Diminishing returns: Crime and incarceration in the 1990s. Washington, DC: The Sentencing Project. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/scans/sp/DimRet.pdf

- Gilbert, A., Siegel, R., Easter, M., Caves Sivaraman, J., Hofer, M., Ariturk, D., Swartz, M. & Swanson, J. (2023, January). Summary of findings from Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD): A multi-site evaluation of North Carolina LEAD programs. Duke University School of Medicine. https://psychiatry.duke.edu/sites/default/files/2023-01/Duke%20LEAD%20Evaluation%20Brief%20Report_Updated%201-24-23.pdf

- Hartmann, F. X. (Ed.). (1988, November). Debating the evolution of American policing. U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/114214.pdf

- Hartman, J. & Hawke, Josephine & Chapman, John. (2008). Traumatic victimization, posttraumatic stress disorder, suicidal ideation, and substance abuse risk among juvenile justice-involved youth. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 1, 75–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361520801934456

- International Association of Chiefs of Police. (2024). Checklist for obtaining officer support. IACP Resources. https://www.theiacp.org/sites/default/files/2024-07/IACP_Officer_BuyIn_Checklist.pdf

- International Centre for the Prevention of Crime. (2015, June). Prevention of Drug-Related Crime Report. https://www.unodc.org/documents/ungass2016/Contributions/Civil/ICPC/Rapport_FINAL_ENG_2015.pdf

- Jones, A. & Sawyer, W. (2019, August). Arrest, release, repeat: How police and jails are misused to respond to social problems. Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/repeatarrests.html

- Korchmaros, J.D. & Bentele, K. G. (2022). Comprehensive evaluation of an innovative collaborative response to the opioid epidemic: Final project findings report. University of Arizona, Southwest Institute for Research on Women.

- Korchmaros, J. D., Bentele, K. G., Granillo, B., & McCollister, K. (2022). Costs, cost savings, and effectiveness of a police-led pre-arrest deflection program. University of Arizona, Southwest Institute for Research on Women. https://sirow.arizona.edu/sites/sirow.arizona.edu/files/DefProg_Outcomes_Report_2022_final.pdf

- Krmpotich, T., Mikulich-Gilbertson, S., Sakai, J., Thompson, L., Banich, M. T., & Tanabe, J. Impaired decision-making, higher impulsivity, and drug severity in substance dependence and pathological gambling. (2015, July–August). Journal of Addiction Medicine, 9(4), 273–80. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000129

- Labriola, M. M., Peterson, S., Taylor, J., Sobol, D., Reichert, J., Ross, J., Charlier, J., & Juarez, S. (2023). A multi-site evaluation of law enforcement deflection in the United States. RAND Corporation. https://doi.org/10.7249/RRA2491-1

- Law Enforcement Action Partnership. (n.d.). Sir Robert Peel's policing principles. https://lawenforcementactionpartnership.org/peel-policing-principles

- Legislative Analysis and Public Policy Association. (2021, September). Model law enforcement and other first responder deflection act. https://legislativeanalysis.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Model-Law-Enforcement-and-Other-First-Responder-Deflection-Act-FINAL.pdf

- Legislative Analysis and Public Policy Association. (2023). Deflection and the deflection pathways. https://legislativeanalysis.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Deflection-Fact-Sheet-FINAL.pdf

- Magnuson, S., Green, C., Dezember, A., & Lovins, B. (2022). Examining the impacts of arrest deflection strategies on jail reduction efforts. Safety and Justice Challenge. https://safetyandjusticechallenge.org/resources/examining-the-impacts-of-arrest-deflection-strategies-on-jail-reduction-efforts/

- Maguire, E. & Wells, W. (Eds.). (2009). Implementing community policing: Lessons from 12 agencies. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing. https://portal.cops.usdoj.gov/resourcecenter/content.ashx/cops-w0746-pub.pdf

- Morrisson, A. (2021, July 23). 50-year war on drugs imprisoned millions of Black Americans. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/war-on-drugs-75e61c224de3a394235df80de7d70b70

- Nembhard, S. & Lima, N. (2022, August 9.) To improve safety, understanding and addressing the link between childhood trauma and crime is key. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/improve-safety-understanding-and-addressing-link-between-childhood-trauma-and-crime-key

- Nyland, J. E., Zhang, A., Balles, J. A., Nguyen, T. H., White, V., Albert, L. A., Henningfield, M. F., & Zgierska, A. (2024, October). Law enforcement-led, pre-arrest diversion-to-treatment may reduce crime recidivism, incarceration, and overdose deaths: Program evaluation outcomes. Journal of Substance Use & Addiction Treatment, 165, 209458. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4682322

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. (2022, June 24). End ‘war on drugs’ and promote policies rooted in human rights: UN experts. https://www.ohchr.org/en/statements/2022/06/end-war-drugs-and-promote-policies-rooted-human-rights-un-experts

- Oliver, W. M. (2017). August Vollmer: The father of American policing. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press.

- Olson, K. (2016, April). Community trust in law enforcement. University of Missouri Institute of Public Policy. https://truman.missouri.edu/sites/default/files/publication/the-ferguson-papers-community-trust-in-law-enforcement.pdf

- Petis, L. (2024, July 15). The crime and safety blind spot: Are mental health disorders fueling criminal activity? R Street. https://www.rstreet.org/commentary/the-crime-and-safety-blind-spot-are-mental-health-disorders-fueling-criminal-activity/

- Pew. (2018, March 8). More imprisonment does not reduce state drug problems. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2018/03/more-imprisonment-does-not-reduce-state-drug-problems

- Pew. (2023, May 16). Racial disparities persist in many U.S. jails. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2023/05/racial-disparities-persist-in-many-us-jails

- Police, Treatment, and Community Collaborative. (2024). Understanding youth deflection & pre-arrest diversion. https://ptaccollaborative.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/PTACC_Youth_Deflection_FINAL_October-2024.pdf

- Ramey, T. & Regier, P. S. (2018, December). Cognitive impairment in substance use disorders. CNS Spectrums, 24(1), 102–113. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852918001426

- Reichert, J., Adams, S., Taylor, J., & del Pozo, B. (2023, February). Guiding officers to deflect citizens to treatment: An examination of police department policies in Illinois. Health & Justice, 11(7), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40352-023-00207-y

- Reichert, J., Labriola, M. M., Peterson, S., & Sobol, D. (2023, June 26). Lake County Illinois deflection program evaluation finds reduced overdoses and property arrests: Research brief. Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority. https://icjia.illinois.gov/researchhub/articles/lake-county-illinois-deflection-program-evaluation-finds-reduced-overdoses-and-property-arrests/

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2024a, May 24). About criminal and juvenile justice. https://www.samhsa.gov/criminal-juvenile-justice/about

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2024b, May 24). The sequential intercept model (SIM). https://www.samhsa.gov/criminal-juvenile-justice/sim-overview

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2023, April 24). Types of treatment. https://www.samhsa.gov/find-support/learn-about-treatment/types-of-treatment

- Taxman, F. S., Shepardson, E. S., & Byrne, J. M. (2004). Tools of the trade: A guide to incorporating science into practice. National Institute of Corrections & Maryland Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services. https://www.gmuace.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/tools-of-the-trade.pdf

- Timko, C., Schultz, N.R., Britt, J., & Cucciare, M. A. (2016, July 29). Transitioning from detoxification to substance use disorder treatment: Facilitators and barriers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 70, 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2016.07.010

- Transform Drug Policy Foundation. (n.d.). Drug diversion in the UK. https://transformdrugs.org/drug-policy/uk-drug-policy/diversion-schemes

- Uhl, G.R., Koob, G.F., & Cable, J. (2019, January 15). The neurobiology of addiction. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1451(1), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13989

- United Nations. (2021). Universal declaration of human rights. https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/2021/03/udhr.pdf

- United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime. (2002). ECOSOC Resolution 2002/13: Action to promote effective crime prevention. https://www.unodc.org/documents/justice-and-prison-reform/crimeprevention/resolution_2002-13.pdf

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. (2016, November). Facing addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s report on alcohol, drugs, and health. Washington, DC: HHS. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-generals-report.pdf

- Verdejo-García, A., Pérez-García, M., & Bechara, A. (2006, January.) Emotion, decision-making and substance dependence: A somatic-marker model of addiction. Current Neuropharmacology, 4(1), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.2174/157015906775203057

- Vitiello, M. (2021). The end of the war on drugs, the peace dividend and the renewed fourth amendment? Oklahoma Law Review, 73(2). https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/olr/vol73/iss2/4

- Volkow, N. D., Koob, G. F., & McLellan, A. T. (2016, January). Neurobiologic advances from the brain disease model of addiction. New England Journal of Medicine, 374(4), 363–371. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1511480

- Vollmer, A. (1936). The police and modern society: Plain talk based on practical experience. University of California Press. p. 118.

- Widom, C. S. (1989). The cycle of violence. Science, 244(4901), 160–166. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.2704995

- Wooditch, A., Tang, L. L., & Taxman, F. S. (2014). Which criminogenic need changes are most important in promoting desistance from crime and substance use? Criminal Justice and Behavior, 41(3), 276. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854813503543

- Yale Medicine. (2022, May 25). How an addicted brain works. https://www.yalemedicine.org/news/how-an-addicted-brain-works

- Yukhnenko, D., Blackwood, N., & Fazel, S. (2020, April). Risk factors for recidivism in individuals receiving community sentences: A systematic review and meta-analysis. CNS Spectrums, 25(2), 252–263. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852919001056

- Zhang, A., Balles, J. A., Nyland, J. E., Nguyen, T. H., White, V. M., & Zgierska, A. E. (2022, June 27). The relationship between police contacts for drug use-related crime and future arrests, incarceration, and overdoses: A retrospective observational study highlighting the need to break the vicious cycle. Harm Reduction Journal, 19, 67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-022-00652-2

AUTHOR

* Guy Farina

TASC’s Center for Health and Justice (USA).

ORCID: 0009-0009-6629-6020.

Requests to authors – Guy Farina, [email protected].

Jac A. Charlier

Hope Fiori

WAIVER

- The ideas, concepts and conclusions set out in this research article do not represent an official position of the European Institute for Multidisciplinary Studies in Human Rights and Sciences - Knowmad Institut gemeinnützige UG (haftungsbeschränkt).

- The content of this article and of this Journal is dedicated to promoting science and research in the areas of sustainable development, human rights, special populations, drug policies, ethnobotany and new technologies. And it should not be interpreted as investment advice.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Thanks to all those who have contributed to the production of this paper.

DONATE AND SUPPORT SCIENCE & HUMAN DIGNITY

IBAN: DE53 1705 2000 0940 0577 43 | BIC/SWIFT: WELADED1GZE |

TITULAR: Knowmad Institut gUG | BANCO: Sparkasse Barnim

http://bit.ly/ShareLoveKI

CC BY-NC 4.0 // 2025 - Knowmad Institut gemeinnützige UG (haftungsbeschränkt)

Contact: [email protected] | Register Nr. HRB 14178 FF (Frankfurt Oder)

This article is part of the Special Issue:

Deflection: A New Horizon for Police,

Public Health, and Community.