Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Human Rights & Science (JMSHRS)

Volume 7, Issue 6, Special Issue on Deflection - V - 2025 | SDGs: 3 | 5 | 10 | 16 | #RethinkProcess ORIGINAL SOURCE ON: https://knowmadinstitut.org/journal/

DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.15227648

Volume 7, Issue 6, Special Issue on Deflection - V, April 2025 | SDGs: 3 | 5 | 10 | 16 |

DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.15227648

Veterans Health Administration Deflection Programming: A Qualitative Study of Providers and Police Officers

Lance Washington

- Center for Innovation to Implementation (Ci2i), VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Menlo Park, CA, USA. ORCID: 0000-0002-2185-1977

Kreeti Singh

- Center for Innovation to Implementation (Ci2i), VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Menlo Park, CA, USA. ORCID: 0009-0005-5358-7938

Katie Stewart

- Veteran Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Washington, DC.

ORCID: 0009-0001-8692-9544

Matthew Stimmel

- Veteran Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Washington, DC. ORCID: 0000-0002-9297-2506

Antonio Harris

- Veteran Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Washington, DC. ORCID: -Unknown-

Andrea K. Finlay*

- Center for Innovation to Implementation (Ci2i), VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Menlo Park, CA, USA. Health Systems Science, Department of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School, Worcester, MA, USA. National Center on Homelessness Among Veterans, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Palo Alto, CA, USA. ORCID: 0000-0003-1284-7092

EN | Abstract:

Objective: Deflection program staff intervene with a person before or during a crisis or a community encounter to connect them with needed healthcare or psychosocial services and prevent their arrest or further interaction with the criminal legal system. As deflection programs develop and expand, there are opportunities to connect veterans in crisis or with other service needs to healthcare. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) supported and trained staff to create and expand deflection partnerships to serve veterans who are at risk for adverse legal or clinical outcomes. This study examined VHA professionals’ experiences with and recommendations for deflection partnerships.

Methods: Virtual semi-structured interviews were conducted with 13 VHA staff from May to June 2024. The primary focus of the interviews was to examine key partners, community-based resources, barriers to successful deflection partnerships, data tracking, and future quality improvement. Transcripts were coded using a priori and emergent codes and analyzed using the framework method.

Results: Most participants were female (56%), white (87%), with a master’s degree (94%), and 10 or more years of employment within VHA (69%). Four themes were identified: (1) deflection partnership characteristics, (2) need for Peer Specialists, (3) VHA and community-based resources and barriers, and (4) data tracking.

Conclusion: Results indicated that VHA staff are highly collaborative, but VHA and community resource gaps, few Peer Specialists dedicated to legal-involved services for veterans, and a lack of data tracking limited successful deflection partnerships. Recommendations to ensure program continuity and expansion include providing more resources and training, hiring Peer Specialists dedicated to legal-involved veterans services and improving data collection and monitoring to facilitate effective deflection partnerships for veterans.

Key Words: Veterans, Criminal Justice, Healthcare, United States Department of Veterans Affairs, SDG 1, SDG 3, SDG 5, SDG 10, SDG 16, SDG.

ES | Abstract:

Objetivo: El personal de los programas de deflexión interviene con una persona antes o durante una crisis o un encuentro en la comunidad para ponerla en contacto con los servicios sanitarios o psicosociales necesarios y evitar su detención o una mayor interacción con el sistema jurídico penal. A medida que los programas de deflexión se desarrollan y amplían, surgen oportunidades para conectar a los veteranos en crisis o con otras necesidades de servicios con la asistencia sanitaria. La Administración de Salud de los Veteranos (VHA, por sus siglas en inglés) apoyó y formó al personal para crear y ampliar las asociaciones de deflexión para atender a los veteranos que corren el riesgo de resultados legales o clínicos adversos. Este estudio examinó las experiencias de los profesionales de la VHA y sus recomendaciones para las asociaciones de deflexión.

Métodos: Se realizaron entrevistas semiestructuradas virtuales con 13 miembros del personal de la VHA entre mayo y junio de 2024. El objetivo principal de las entrevistas era examinar los socios clave, los recursos basados en la comunidad, las barreras para el éxito de las asociaciones de deflexión, el seguimiento de datos y la futura mejora de la calidad. Las transcripciones se codificaron utilizando códigos a priori y emergentes y se analizaron utilizando el método del marco.

Resultados: La mayoría de los participantes eran mujeres (56%), caucasicos (87%), con un máster (94%) y 10 o más años de empleo en la VHA (69%). Se identificaron cuatro temas: (1) características de la asociación de deflexión, (2) necesidad de Especialistas Pares, (3) recursos y barreras de la VHA y de la comunidad, y (4) seguimiento de datos.

Conclusión: Los resultados indicaron que el personal de la VHA es muy colaborador, pero las lagunas en los recursos de la VHA y de la comunidad, el escaso número de especialistas dedicados a los servicios jurídicos para veteranos y la falta de seguimiento de los datos limitaron el éxito de las asociaciones de deflexión. Las recomendaciones para garantizar la continuidad y la expansión del programa incluyen proporcionar más recursos y formación, contratar a Especialistas Pares dedicados a los servicios para veteranos con implicación legal y mejorar la recopilación y el seguimiento de datos para facilitar asociaciones de deflexión eficaces para los veteranos.

Palabras clave: Veteranos, Justicia penal, Sanidad, Departamento de Asuntos de Veteranos de los Estados Unidos, ODS 1, ODS 3, ODS 5, ODS 10, ODS 16, ODS.

INTRODUCTION

Military veterans may experience a range of challenges, such as untreated mental health and substance use disorder conditions, housing and financial instability, and difficulty reintegrating into civilian life, which can lead to crises and interaction with law enforcement (Finlay, Owens, et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2024). Although the existing Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Veterans Justice Programs (VJP) support veterans in courts, jails, and prisons, these interventions occur after a veteran has been arrested (Blue-Howells et al., 2013). In the time before arrest and legal involvement, such as crisis moments and other first responder interactions, there are opportunities to connect veterans to VHA healthcare services while reducing distress and suicidal ideation (Britton et al., 2023). Intervening with veterans prior to or at the time of arrest may prevent incarceration, which is linked with an elevated risk of suicide and overdose mortality (Finlay et al., 2022; Palframan et al., 2020).

The Veteran-Sequential Intercept Model (V-SIM) depicts points along the criminal legal continuum where interventions can occur to mitigate the risk of current or future involvement with the legal system (Blue-Howells et al., 2013). Deflection focuses on non-crisis deflection (intercept 0), which includes crisis lines and the crisis care continuum, and pre-arrest deflection (intercept 1), which includes crisis teams and arrest. Interventions at these intercept points are designed to connect a person interacting with law enforcement and first responders with needed healthcare and psychosocial services, even if no arrest occurs (Abreu et al., 2017; Charlier & Reichert, 2020). Deflection partnerships contain many of the same elements as Crisis Intervention Training (CIT) and co-responder models. CIT equips law enforcement and first responders with the skills to recognize and de-escalate mental health crises, understand mental illness, and connect adults in crisis with the appropriate services (Mok et al., 2018; Shia et al., 2013). Co-responder models pair law enforcement officers with mental health professionals to divert individuals from arrest to appropriate services during crises (Ross & Taylor, 2022). Deflection services can include mental health treatment, substance use disorder treatment, or programs to address housing or food insecurity.

In 2023, the VJP expanded deflection training and partnerships with VHA police, community law enforcement, and healthcare providers to intervene with veterans during crises and other first responders' interactions, recognizing the importance of working farther upstream along the criminal legal continuum. VJP trained over 500 VHA staff from all VHA facilities on deflection practices, in a series titled, Preparing Interdisciplinary Teams to Partner with Community Law Enforcement-Based Deflection Initiatives Serving Veterans. Each training included at least one VJP Specialist, one mental health provider, and one VHA police officer from each VHA facility. A previous environmental scan of VJP after the training initiative was underway indicated that 96% of interactions between VJP Specialists and law enforcement were informal and buy-in was a large barrier to successful deflection (Washington et al., 2024). The scan did not include an in-depth analysis of training needs and emerging practices for broader adoption within VHA and was administered prior to all training being completed. The current study aimed to examine VHA staff experiences with and recommendations for future VHA deflection partnerships.

WELL-BEING, ASSESSMENT, AND PROTECTION OF IMPACTED CHILDREN

The adoption of best practices that address the impact of opioid use and overdose on children (and other family members) is needed. In 2017, there were over 2 million youth who had a parent with an opioid use disorder or who themselves had an opioid use disorder (Brundage et al., 2019). Adolescents and young adults living in homes where opioids are accessible are at higher risk of overdose themselves—namely, young adults showed a 2-fold increase in overdose risk when they had a family member with an opioid prescription and a 5-fold increase when they had an opioid prescription (Nguyen et al., 2020). In addition to overdose risk, families with familial opioid use and low cohesion have lower communication and well-being relative to families with no opioid use or opioid use and high family cohesion (Alhaussain et al., 2019).

Youth living in households with opioid misuse are at a higher risk for mental health problems, the development of a substance use disorder, and family dissolution (Winstanley & Stover, 2019) while the spouses of people using opioids are at the greatest risk for developing an opioid use disorder (Ali et al., 2019). The downstream consequences of familial opioid use are noteworthy and may be partially redressed through opioid response models that prioritize family-centered practices that support family cohesion.

National organizations such as the National Alliance for Drug Endangered Children (National Alliance for Drug Endangered Children, 2024) can provide useful guidance related to understanding the physical and emotional harm that illegal drug use, possession, manufacturing, and distribution have on drug-endangered children. By leveraging organizational expertise in trauma-informed care, deflection models may be able to provide actionable recommendations for how these practices can be implemented alongside existing opioid response models. In fact, initiatives like Handle with Care—a program that enables police officers to recognize trauma and direct children to appropriate services—have begun to delineate the challenges of addressing the needs of at-risk children (see Wisdom et al., 2022). The Police, Treatment and Community Collaborative (PTACC) also has identified problems associated with addressing the needs of impacted children. As outlined in their Children and Families Strategy Area, PTACC stresses the importance of incorporating a variety of organizations and agencies to address family and children’s needs. This could include, for example, services for food or housing insecurities, substance use and mental health, educational support, couple’s therapy, building familial cohesion, and healthcare resources.

METHODS

Design

An exploratory qualitative study using semi-structured interviews of VHA staff was conducted. This study was approved as a quality improvement project.

Recruitment procedures

Three steps were used to recruit study participants. First, VJP Specialists were recruited using convenience sampling from a national Veterans Justice Programs listserv. They were eligible for recruitment if they were VJP Specialists during the study period and participated in the deflection training or initiatives. Interested Specialists contacted the research team to participate. Second, eight sites with more developed deflection partnerships were selected using purposive sampling. Nine Specialists and 10 VHA Police Officers from these sites who participated in deflection training were identified from the training list and directly contacted via email. Third, snowball sampling was used to recruit additional participants. VJP Specialists who participated in the study were asked to email additional Specialists, mental health providers, and law enforcement officers they worked with who might be willing to participate.

The target number of interviews was one interview per site per type of staff member (VJP Specialist, Police Officer, mental health provider). Recruitment ended in June 2024 after one Specialist from each target site was interviewed and saturation was achieved. The target number of Police Officers was not reached prior to the end of recruitment. No mental health providers agreed to participate. Per VHA policies, staff were not offered compensation for participation.

Interview Guide

One interview guide was developed for all participants. Participants were asked to report on deflection partnerships at their local VHA medical center. Topics assessed were key partnerships, community-based resources, barriers to deflection partnerships, data tracking, and future quality improvement.

Data collection

Pilot testing occurred in March 2024 by two authors (LW and AKF) in separate interviews with two VJP staff members familiar with deflection partnerships. Refinements were made after pilot testing under the guidance of the senior author (AKF). Data collection was conducted between May 2024 and June 2024. Interviews were conducted virtually and lasted approximately 45 minutes.

Data analysis

All interviews were audio recorded using the Microsoft Teams platform, then transcribed, de-identified, and checked for quality. All transcripts were uploaded to Atlas.ti Version 23 (Atlas.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, 2019). Framework analysis was used to analyze the transcripts (Furber, 2010). Interview transcripts were coded using a code list that included a priori categories and codes identified during the coding process. Next, data were analyzed within the context of the topic areas. Finally, key points across all participants were identified. The research team did not send results to participants for feedback.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

There were 13 VJP Specialists and 3 VHA Police Officers from 13 VHA facilities who participated: 7 participants were from 5 target sites and 6 participants were from 8 non-target sites. Most participants were female (56%) and white (87%). Almost all participants had a master’s degree (94%), and about two thirds worked 10 or more years at VHA (69%). Participants were employed at VHA facilities in the Northeast (31%), South (25%), Midwest (31%), and West (13%).

Deflection Partnership Characteristics

Both VJP Specialists and VHA Police Officers described deflection as a collaborative process where veterans are diverted away from the criminal legal system and towards appropriate VHA healthcare or community services. VJP Specialists and VHA Police Officers mentioned each other as the most important key partners. VJP Specialists often cited law enforcement as their primary partner due to their frontline role in encountering veterans in crisis. VHA Police Officers highlighted VJP Specialists as the most successful partner for deflection due to their ability to facilitate connection to VHA healthcare and treatment. All VHA Police Officers were involved in CIT with VJP Specialists and were veterans themselves.

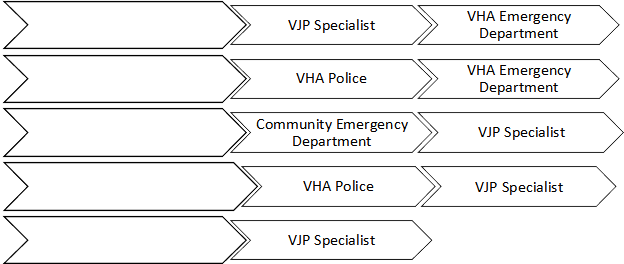

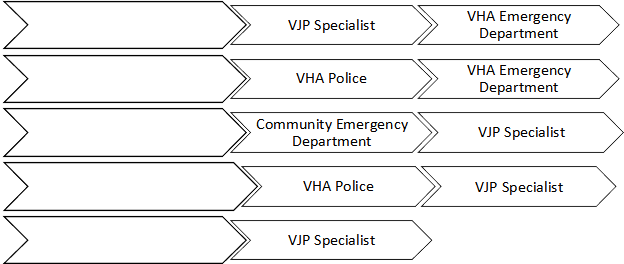

Both VJP Specialists and VHA Police Officers emphasized the critical role of community law enforcement in facilitating the deflection process, which commonly occurred though five main pathways. Figure 1 illustrates the key partners in the deflection process.

A VHA Police Officer (participant #16) highlighted their facilitating role within the deflection below:

“Sometimes I'll get a phone call from [community] police saying we have a veteran…we're thinking about bringing in and the first thing I do is I need name, date of birth, social and service branch and years and what's the complaint, then I try to go to coordinate with admissions or through or through the VJO. Is this a person actually a veteran? Because we don't want to waste time…we're intermediaries, that's a lot of what I do is intermediary.”

Figure 1: Common Deflection Processes Between Community Partners and VHA

Need for Peer Specialists

VJP Specialists emphasized Peer Specialists as valuable in engaging veterans in healthcare, but most VJP Specialists stated that their medical centers do not have a VJP-specific Peer Specialist. Most VJP Specialists reported that Peer Specialists primarily worked within mental health or homeless program offices. VJP Specialists expressed the need for Peer Specialists to assist in training, peer education, and providing direct non-clinical support to veterans, which would help in building trust and more personalized care. One VJP Specialist (participant #10) stated:

"They do some really cool stuff…like a bowling night where they get to go bowling and it's free and they don't have to pay and...a pizza night and stuff like that...it's been very good for those particular veterans who at first were a little resistant….increasing the peer support would probably be helpful”

Similar to VJP Specialists, all three VHA Police Officers endorsed Peer Specialists as a critical component of deflection partnerships. One officer who works directly with a VHA Peer Specialist stated that Peer Specialists were an example that adults with former criminal legal involvement can be gainfully employed.

VHA and Community-Based Resources and Barriers

VJP Specialists identified various VHA and community resources and barriers to deflection partnerships. Within VHA, resources for successful deflection included VHA Police, VHA emergency rooms, ongoing CIT training, and pre-existing relationships between VHA and community partners. Community-based resources included law enforcement and mental health co-response teams, Peer Specialists, and crisis stabilization units. A desired resource among VJP Specialists included 24/7 VHA emergency and crisis services at all medical centers, especially in rural areas. Barriers to buy-in and successful deflection partnerships were lack of VHA emergency departments in certain jurisdictions, no pre-existing relationship with community partners, and HIPAA restrictions that limited communication of vital health information. Another barrier was that relationship building with community partners was classified as non-clinical work within VHA, resulting in fewer documented clinical encounters for VJP Specialists.

Some VJP Specialists noted that rural areas face distinct challenges. For example, long driving distances to VHA medical centers were noted as a challenge to deflection partnerships with that limited coordination between key partners. Limited resources in both VHA and community were noted as a challenge to rural areas, whereas in urban areas VHA medical centers tended to be better resourced. One VJP Specialist (participant #9) stated:

“I think you gotta really do a good review of what you have available and be realistic for what you can really accomplish depending on the geography and the population in…your catchment area. I think that big VA has put this thing out as deflection, but they haven't taken into account the differences in rural versus urban…I mean [rural state]…is a big state, but then you talk about [other rural states] where it's even farther to do stuff, and there's even less resources.” -VJP Specialist

VHA Police Officers echoed many of the same resources for successful deflection partnerships but highlighted slightly different barriers. For VHA Police Officers, critical resources cited included VJP Specialists, CIT training, social workers embedded in law enforcement facilities, and collaborative models like the co-responder model that aim to address crises and provide ongoing support. Community based resources, such as community forums and steering committees, were highlighted as useful opportunities to identify immediate community needs. VHA Police Officers emphasized that the large presence of veterans in community law enforcement roles was a vital resource for successful deflection partnerships. Barriers to buy-in and successful deflection partnerships were lack of legal jurisdiction as VHA Police Officers cannot respond in a law enforcement capacity off VA property.

Data Tracking

Deflection engagement tracking mechanisms were underutilized by VJP Specialists. The most utilized mechanisms to record deflection encounters and partnerships among Specialists were the Homeless Operations Management System (HOMES; used to track and analyze services provided to veterans who are homeless or at risk of homelessness) and Administrative Data Tracking System (ADTS; a system for managing and monitoring administrative data related to program development). Data tracked by VJP Specialists was not standardized across VHA sites and included the number of phone calls and emails with key partners, the number of veterans they encountered, and veterans’ contact information including name, email address, and phone number.

Data tracked by VHA Police Officers was not standardized, but all VHA Police Officers tracked some data. These data included number of veterans brought into the emergency department by community law enforcement partners, which law enforcement officer brought them in, why the veteran was brought in (e.g., suicidal, homicidal ideations, and detox), whether the officer was trained in CIT and/or a member of a Veteran Response Team, and if the deflection outcome resulted in an arrest or receipt of services.

Other outreach data tracked by VHA Police Officers included the number and type of people trained in CIT, the number of conference calls with partners, success stories, and how many calls they are responding to. Barriers to data tracking included a lack of integrated data systems for tracking and coordinating care between health and criminal legal systems and nonintegrated systems for data tracking. No data on veterans who were not eligible for VHA healthcare were tracked by VJP Specialists or VHA Police Officers.

DISCUSSION

Our results suggest that there were three key study findings. First, VHA and community partnerships were critical to collaborations but were hindered by a lack of existing relationships and limited resources. Second, despite being highlighted as having a vital role in successful deflection efforts, most VHA facilities lacked a VJP-dedicated Peer Specialist. Finally, real-time data tracking and the use of standardized metrics were mentioned as needed to measure and monitor successful deflection.

Collaboration and communication across partnerships were cited as key to successful deflection partnerships. Relationships between VJP Specialists, VHA, and community police were critical to connecting veterans from their law enforcement encounters to the appropriate person or healthcare setting (e.g., emergency department), consistent with prior research that highlighted VHA police as important to linking veterans to healthcare (Tsai et al., 2023). Similarly, almost all community-based first responder programs reported having at least two collaborative partners and nearly half had three collaborative partners (Ross & Taylor, 2022).

Relationship building with community partners was limited because it was classified as non-clinical work and may require adjusting system-level priorities and re-occurring training to address this barrier. Although developing and maintaining partnerships with criminal justice agencies is highlighted in the VJP’s Strategic Plan (Veterans Justice Programs, 2020), aligning workforce clinical productivity with this priority may yield more success at relationship building.

Additional training to VHA leadership and staff on deflection initiatives in general, and the value community partnerships bring towards reducing risks of suicide and overdose may help address this barrier and could be incorporated in the existing crisis training VHA police officers receive as part of onboarding (Weaver et al., 2022).

In 2023, trainings of interdisciplinary teams of a VJP Specialist, a VHA police officer, and a VHA mental health provider were conducted to build skills and knowledge in deflection partnerships (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2023). This training could be offered on a reoccurring basis and the training impact could be more formalized in reporting to individual facility leadership. Given the elevated risks of suicide and overdose among veterans with legal involvement (Finlay et al., 2022; Palframan et al., 2020) and that over half of veterans who died by suicide in 2020 did not use VHA services (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2022), efforts to outreach to the community are imperative.

A number of other training opportunities and resources in VHA are ongoing that support the sustainability and growth of deflection partnerships, including a deflection community of practice call occurring every other week for a limited time, a national VJP deflection toolkit, and a statewide coordination effort with communities on VHA resources to help identify veterans during crisis encounters. The Center for Health and Justice also offers numerous deflection partnership training resources (Treatment Alternatives for Safe Communities, 2025).

In rural areas, a lack of 24/7 emergency services and crisis stabilization centers were highlighted as barriers to deflection. Partnerships may be challenging to cultivate without VHA being able to offer the resources a community needs. Certified Community Behavioral Health Centers offer robust behavioral health services, including healthcare for veterans, and may be an option to increase crisis services in rural areas (Sulzer et al., 2024). Long driving distances to VHA medical centers were also noted as a challenge in rural areas.

Utilizing the Veterans Comprehensive Prevention, Access to Care, and Treatment (COMPACT) Act (Veterans COMPACT Act, 2020), which allows any veteran experiencing a suicidal crisis to access VHA or non-VHA emergency department care, may be one option to access services in the community when the VHA medical center is farther away.

However, as many respondents noted a lack of 24/7 emergency services at both VHA and the community, the COMPACT Act may not be a solution in all regions of the country. Although VHA typically has more healthcare resources than communities, a lack of healthcare providers and services, particularly for behavioral health, remains a persistent challenge across the US. To ensure the sustainability and scalability of deflection partnerships, resources at VHA facilities and in communities will need to be expanded. Connecting veterans to VHA services rather than the community, when appropriate, may free up community resources to be deployed effectively to other veterans and non-veterans. Furthermore, creative thinking of existing resources will be required. For example, libraries and other existing community resources may be utilized in deflection partnerships to provide information and support to veterans who are struggling and may be in crisis.

Peer Specialists were highlighted as a key role in deflection, but most VHA partnerships did not have a VJP-based Peer Specialist. Despite historical challenges of hiring delays and insufficient funding for peers (Chinman et al., 2012), the VHA is expanding the Peer Specialist role more broadly within the healthcare system and specifically within VJP (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2024). National VHA training for peers is offered in 13 core competencies to maximize their effectiveness with veterans (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2019). Some of these core competencies include recovery principles, such as an understanding and use of SAMHSA’s guiding principles of recovery; peer support practices, such as conveying hope that recovery is possible; cultural competence, such as interacting sensitively and effectively with people from various cultural backgrounds; communication, such as validating others’ experiences and feelings; recovery and personal wellness goals, assist veterans to articulate recovery goals and identify barriers to achieving their goals; holistic approach to services, such as knowing resources and services in VHA that support veterans’ holistic health; and managing crisis and emergency situations, such as knowing suicide prevention strategies and how to engage clinical providers when needed. These core competencies are consistent with those from the Substance Abuse and Mengal Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) recommended for peer workers in behavioral health services (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015).

As part of their professional role, VHA peers are required to obtain national or state certification as peers within a year of employment. Community-based deflection programs found that peers were valuable to their teams, with benefits ranging from maintaining communication, provided hope, and encouraging and supporting clients to connect with treatment and housing services (Altarum, 2021). As veteran peers join deflection partnerships, it will be useful to collect information on their value to support future implementation of peers as key partners.

Standardized metrics and processes for collecting and reporting data are critical to determine the programmatic needs within a community or healthcare system, allocate resources, and monitor existing deflection partnerships to ensure they are effective (Center for Health and Justice at TASC, 2013; Justice Center, 2019). However, study participants reported that data collection and standardized metrics were underutilized or non-existent, consistent with other diversion programs (Center for Health and Justice at TASC, 2013).

To establish baseline deflection data, basic information such as the number of veterans diverted to VHA or community healthcare and follow-up treatment rates and services of VHA or community healthcare, similar to what is recommended for Veterans Treatment Courts (Finlay, Clark, et al., 2019), and cost effectiveness data, such as how much money is being saved by reduced hospital or emergency department visits, may shed some light on the effectiveness of these partnerships. The Police, Treatment, and Community Collaborative also has recommended measures, including the number of referrals made by individuals and agencies, the proportion of individuals referred for treatment that are assessed and being treatment, and the change in jail admissions over time (PTACC: Police, Treatment, and Community Collaborative, 2018).

A single-site VHA study on a veteran deflection program used VHA police records and healthcare records to examine the program’s effectiveness and may serve as a model for data tracking that could be conducted at other VHA sites (Tsai et al., 2023). However, this was the only veteran deflection evaluation of which we are aware. Evaluations of community-based deflection programs are similarly rare with only 17% of over 200 first-responder deflection programs reporting conducting an evaluation (Ross & Taylor, 2022). The jail diversion literature may offer guidance on measurable outcomes. For example, a Texas study found reductions in reoffending and improvements in employment rates among jail diversion participants (Mueller-Smith & T. Schnepel, 2021).

Based on the V-SIM (Blue-Howells et al., 2013), deflection partnerships are theorized to prevent or reduce the risk of further involvement in the criminal legal system. Longitudinal data tracked is needed to determine whether these programs are achieving this goal. Privacy laws and policies can create challenges to improving data collection and tracking because of limitations on data sharing, confusion over who is responsible for the data and privacy, and what privacy laws and restrictions are applicable (Worobiec et al., 2023). Although at the early stages, deflection programs are developing internationally, including in the United Kingdom and parts of Africa (PTACC: Police, Treatment, and Community Collaborative, 2024a, 2024b), and these programs may have different data priorities and laws and policy they must follow based on where they are located.

As deflection evolves in the United States and internationally, bringing key partners together to define and standardize data collection and develop guidance on best practices to implement integrated data systems that respect privacy will be necessary to ensure these programs are successful.

LIMITATIONS

Although this study provides valuable insights into the current state and future training needs of deflection partnerships within VHA, there are a few limitations. First, our study included three VHA Police Officers and may not have reached saturation. However, responses from VHA Police Officers were similar to results from other diversion studies (Anderson et al., 2022; Wood et al., 2021), suggesting that saturation was reached. Second, we were not able to recruit VHA mental health professionals so we do not know how they experience deflection partnerships and their recommendations for improving these services. Third, interview participants came from 13 sites, all of which vary in resources and practices and we did not collect detailed information on the steps and protocols within deflection partnerships, nor is there standardization of these partnerships currently. Future studies at selectively targeted sites with similar levels of resources and programmatic development may yield additional recommendations that were unidentified in the current study. Comprehensive studies of the development of veteran deflection partnerships, such as a survey modeled after a study of first responder deflection programs (Ross & Taylor, 2022), may provide guidelines for communities building and growing these partnerships.

CONCLUSION

Although deflection programs are developing across the VHA system, there are VHA and community resource gaps, a lack of availability of Peer Specialists, and minimal data tracking and standardization. To ensure deflection partnership continuity and expansion, more resources and training will need to be offered, including for peers. Robust data collection and monitoring across collaborative partners will help determine programmatic needs and resource allocation and ensure the effectiveness of deflection partnerships for veterans.

REFERENCES

- Abreu, D., Parker, T. W., Noether, C. D., Steadman, H. J., & Case, B. (2017). Revising the paradigm for jail diversion for people with mental and substance use disorders: Intercept 0. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 35(5–6), 380–395. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2300

- Altarum. (2021). Peer support in first responder-led diversion and deflection programs: Necessary tools int eh fight against COVID-19. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Comprehensive Opioid, Stimulatn, and Substance Abuse Program. https://www.cossup.org/Content/Documents/Articles/Altarum_Peer_Support_in_Diversion_Programs.pdf

- Anderson, E., Shefner, R., Koppel, R., Megerian, C., & Frasso, R. (2022). Experiences with the Philadelphia police assisted diversion program: A qualitative study. International Journal of Drug Policy, 100, 103521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103521

- Atlas.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH. (2019). Atlas.ti Version 8 [Computer Software] [Computer software]. Scientific Software Development.

- Blue-Howells, J. H., Clark, S. C., van den Berk-Clark, C., & McGuire, J. F. (2013). The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Veterans Justice Programs and the sequential intercept model: Case examples in national dissemination of intervention for justice-involved veterans. Psychological Services, 10(1), 48–53. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029652

- Britton, P. C., Karras, E., Stecker, T., Klein, J., Crasta, D., Brenner, L. A., & Pigeon, W. R. (2023). Veterans Crisis Line call outcomes: Treatment contact and utilization. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 64(5), 658–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2023.01.024

- Center for Health and Justice at TASC. (2013). No entry: A national survey of criminal justice diversion programs and initatives. Author. https://www.centerforhealthandjustice.org/tascblog/Images/documents/Publications/CHJ%20Diversion%20Report_web.pdf

- Charlier, J., & Reichert, J. (2020). Introduction: Deflection—Police-led responses to behavioral health challenges. Journal for Advancing Justice, III, 1–13.

- Chinman, M., Salzer, M., & O’Brien-Mazza, D. (2012). National survey on implementation of peer specialists in the VA: Implications for training and facilitation. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 35(6), 470–473. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0094582

- Department of Veterans Affairs. (2019). VHA Peer Support staff competencies. Author.

- Department of Veterans Affairs. (2023). Memorandum: Training Interdisciplinary VA Medical Center (VAMC) Teams to Partner with Community Law Enforcement-Based Deflection Initiatives (VIEWS 9447517).

- Department of Veterans Affairs. (2024, April). VHA directive 1162.06. Under Secretary for Health.

- Finlay, A. K., Clark, S., Blue-Howells, J., Claudio, S., Stimmel, M., Tsai, J., Buchanan, A., Rosenthal, J., Harris, A. H. S., & Frayne, S. M. (2019). Logic model of the Department of Veterans Affairs’ Role in Veterans Treatment Courts. Drug Court Review, 2.

- Finlay, A. K., Owens, M. D., Taylor, E., Nash, A., Capdarest-Arest, N., Rosenthal, J., Blue-Howells, J., Clark, S., & Timko, C. (2019). A scoping review of military veterans involved in the criminal justice system and their health and healthcare. Health Justice, 7(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40352-019-0086-9

- Finlay, A. K., Palframan, K. M., Stimmel, M., & McCarthy, J. F. (2022). Legal system involvement and opioid-related overdose mortality in U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs patients. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 62(1), e29–e37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2021.06.014

- Furber, C. (2010). Framework analysis: A method for analysing qualitative data. African Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health, 4(2), 97–100. https://doi.org/10.12968/ajmw.2010.4.2.47612

- Justice Center. (2019). Behavioral health diversion interventions: Moving from individual programs to a systems-wide strategy. The Council of State Governments. https://csgjusticecenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Diversion-conecept-paper.pdf

- Mok, C., Weaver, C., Rosenthal, J., Pettis, T., & Wickham, R. (2018). Augmenting Veterans Affairs police mental health response: Piloting diversion to health care as risk reduction. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management, 5(4), 227–237.

- Mueller-Smith, M., & T. Schnepel, K. (2021). Diversion in the Criminal Justice System. The Review of Economic Studies, 88(2), 883–936. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdaa030

- Palframan, K. M., Blue-Howells, J., Clark, S. C., & McCarthy, J. F. (2020). Veterans Justice Programs: Assessing population risks for suicide deaths and attempts. Suicide Life Threat Behav, 50(4), 792–804. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12631

- PTACC: Police, Treatment, and Community Collaborative. (2018). PTAC recommended core measures for five pre-arrest diversion frameworks. Author. https://ptaccollaborative.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/PTACC_CoreMeasures-3.pdf

- PTACC: Police, Treatment, and Community Collaborative. (2024b). PTACC African leaders deflection summit. https://ptaccollaborative.org/ptacc-african-leaders-deflection-summit/

- PTACC: Police, Treatment, and Community Collaborative. (2024a). PTACC UK. https://ptaccollaborative.org/ptacc-uk/

- Ross, J., & Taylor, B. (2022). Designed to do good: Key findings on the development and operation of first responder deflection programs. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 28(Supplement 6), S295–S301. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000001578

- Shia, S. S., Miller, M. J., Swensen, A. B., & Matthieu, M. M. (2013). Veterans Justice Outreach and Crisis Intervention Teams: A Collaborative Strategy for Early Intervention and Continuity of Care for Justice-Involved Veterans. Military Behavioral Health, 1(2), 136–145.

- Singh, K., Timko, C., Yu, M., Taylor, E., Blue-Howells, J., & Finlay, A. K. (2024). Scoping review of military veterans involved in the criminal legal system and their health and healthcare: 5-year update and map to the Veterans-Sequential Intercept Model. Health & Justice, 12(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40352-024-00274-9

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2015). Core competencies for peer workers in behavioral health services. Author. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/programs_campaigns/brss_tacs/core-competencies_508_12_13_18.pdf

- Sulzer, S. H., Meier, C., Bopp-Williams, N., Cook, P., & Prest, L. (2024). Challenges and opportunities for rural certified community behavioral health clinics. Journal of Rural Mental Health, 48(2), 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1037/rmh0000259

- Treatment Alternatives for Safe Communities. (2025). TASC Center for Health and Justice. https://www.tasc.org/tascweb/home.aspx

- Tsai, J., Gonzalez, C., Szymkowiak, D., Stewart, K., Dillard, D., Whittle, T., & Woodland, P. (2023). Evaluating veterans response teams and police interventions on Veterans’ Health Care utilization. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 29(3), 387–391. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000001718

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2022). National veteran suicide prevention annual report. Author. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2022/2022-National-Veteran-Suicide-Prevention-Annual-Report-FINAL-508.pdf

- Veterans COMPACT Act, Pub. L. No. 116–214, H.R.8247 (2020).

- Veterans Justice Programs. (2020). Veterans Justice Programs: Strategic goals, objectives, actions and measures (Fiscal Years 2019-2023).

- Washington, L., Singh, K., Stewart, K., Firesheets, K., Charlier, J., & Finlay, A. K. (2024). Veterans deflection: Not waiting for military veterans to be arrested or in crisis before we act. In Handbook on Contemporary Issues in Health, Crime, and Punishment (1st ed., pp. 469–492). Routledge.

- Weaver, C. M., Rosenthal, J., Giordano, B. L., Schmidt, C., Wickham, R. E., Mok, C., Pettis, T., & Clark, S. (2022). A national train-the-trainer program to enhance police response to veterans with mental health issues: Primary officer and trainer outcomes and material dissemination. Psychological Services, 19(4), 730–739. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000520

- Wood, J. D., Watson, A. C., & Barber, C. (2021). What can we expect of police in the face of deficient mental health systems? Qualitative insights from Chicago police officers. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 28(1), 28–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12691

AUTHOR

* Andrea K. Finlay*

- Center for Innovation to Implementation (Ci2i), VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Menlo Park, CA, USA. Health Systems Science, Department of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School, Worcester, MA, USA. National Center on Homelessness Among Veterans, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Palo Alto, CA, USA. ORCID: 0000-0003-1284-7092

Requests to authors – Andrea Finlay, [email protected], 795 Willow Rd (152-MPD), Menlo Park, CA, 94025, USA

Lance Washington

- Center for Innovation to Implementation (Ci2i), VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Menlo Park, CA, USA. ORCID: 0000-0002-2185-1977

Kreeti Singh

- Center for Innovation to Implementation (Ci2i), VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Menlo Park, CA, USA. ORCID: 0009-0005-5358-7938

Katie Stewart

- Veteran Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Washington, DC. ORCID: 0009-0001-8692-9544

Matthew Stimmel

- Veteran Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Washington, DC. ORCID: 0000-0002-9297-2506

Antonio Harris

- Veteran Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Washington, DC. ORCID: -Unknown-

AUTHOR NOTE

Ethical Statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This study was supported by the Veterans Justice Programs, Homeless Programs Office.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

WAIVER

- The ideas, concepts and conclusions set out in this research article do not represent an official position of the European Institute for Multidisciplinary Studies in Human Rights and Sciences - Knowmad Institut gemeinnützige UG (haftungsbeschränkt).

- The content of this article and of this Journal is dedicated to promoting science and research in the areas of sustainable development, human rights, special populations, drug policies, ethnobotany and new technologies. And it should not be interpreted as investment advice.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Thanks to all those who have contributed to the production of this paper.

DONATE AND SUPPORT SCIENCE & HUMAN DIGNITY

IBAN: DE53 1705 2000 0940 0577 43 | BIC/SWIFT: WELADED1GZE |

TITULAR: Knowmad Institut gUG | BANCO: Sparkasse Barnim

http://bit.ly/ShareLoveKI

CC BY-NC 4.0 // 2025 - Knowmad Institut gemeinnützige UG (haftungsbeschränkt)

Contact: [email protected] | Register Nr. HRB 14178 FF (Frankfurt Oder)

This article is part of the Special Issue:

Deflection: A New Horizon for Police,

Public Health, and Community.